A (mostly) automated release process

Automate whatever you can automate and share the responsibility for the remaining tasks.

This blog post is part of a series where I share our migration from monolithical applications (each with their own source repository) deployed on AWS to a distributed services architecture (with all source code hosted in a monorepo) deployed on Google Cloud Platform.

- Part 1 (this post): “A monorepo, GitHub Flow and automation FTW”

- Part 2: “One vs. many — Why we moved from multiple git repos to a monorepo and how we set it up”

- Part 3: “A (mostly) automated release process”

- Part 4: “Our approach to software development consistency”

What is a “release process”?

Release management is the process of managing, planning, scheduling and controlling a software build through different stages and environments; including testing and deploying software releases.

Source: Wikipedia

Woah… That’s one long-a** sentence, it reminds me of German sentences I wrote in my essays when I grew up in 🇨🇭.

A slightly less verbose way of putting it:

“How to get code from my laptop to production.”

Source: Me

In the end, it’s all about code and along the journey we want to do certain things to or with the code. Such as:

- KISS; tools like ESLint can help with that.

- Keep consistent formatting. Prettier is your must-have tool here.

- Run tests.

- Bundle reusable code into packages and deploy them to NPM.

- Build services that leverage the aforementioned packages.

- Give stakeholders a chance to review code in some more or less safe environment, often referred to as “staging”.

- Take that reviewed code and deploy it to where it really matters: 🥁 …

the production environment 🎉

Why “automated”?

Great question, glad you asked. Mainly, because we can. More importantly though, most developers I know spend day after day writing code because they feel good when they release software that helps others (your mileage may vary). Rarely (never?) have I met passionate developers who say, “You know, I simply love to manually ssh into my virtual machine, run git pull, then sh ./scripts/release-carefully.sh --production=true and hope for the best 🤞”.

As a rule of thumb,

If a task can be automated in roughly the time it takes to execute it manually, automate it. Now.

Here’s why: Passionate software engineers want to spend their time dealing with more important situations. Automating mundane tasks should be a priority for anyone in the software industry. Let’s do some math and see why:

- Manually deploying a new feature to your staging environment takes 21 minutes, give or take.

- You do that once a day, five days a week.

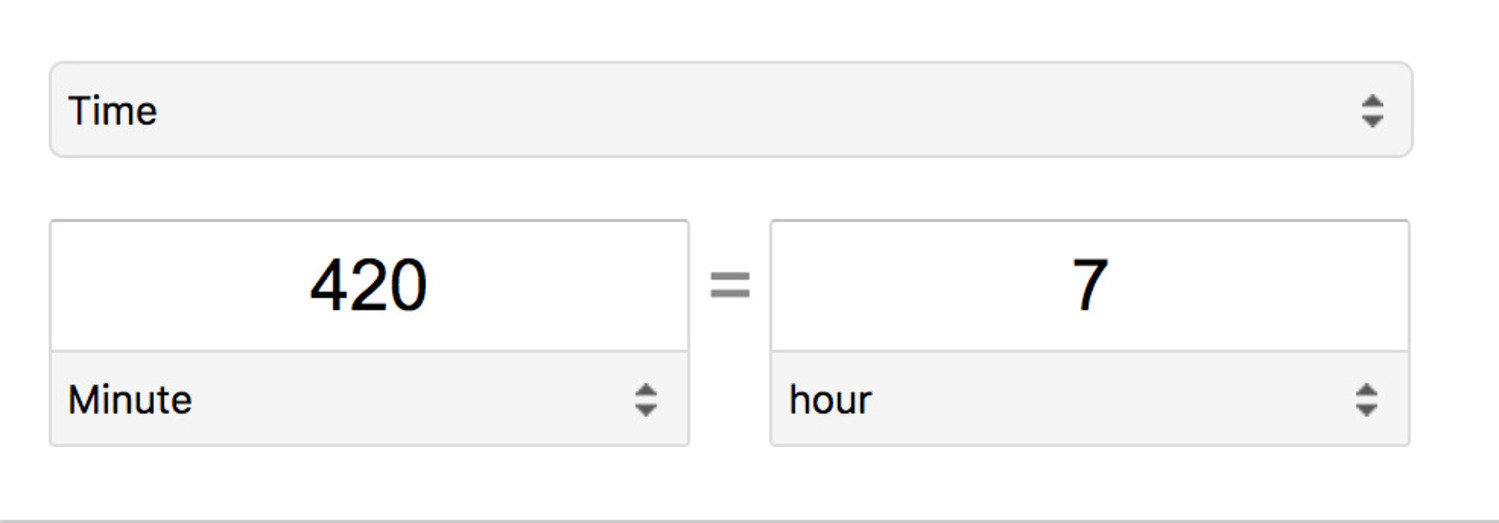

- Here’s the math: 21 minutes x 5 days per week = 105 minutes per week x 4 weeks = 420 minutes per month.

Source: Google

Seven hours per month is **1 full business day**. As an exercise for the reader, you could add the time it takes to deploy to production plus dealing with potential hotfix deployments.

Let’s say you end up with 2 to 3 business days as the grand total. Instead of spending that time month after month, invest it into writing automation scripts. In the second month, you’ll have 2 to 3 extra business days where you can mentor a more junior team member or organize a lunch & learn to share the ins and outs of your release automation script with the community in your city 🙌.

Why “mostly”?

I have yet to encounter a 100% automated release process for a software application. While this is certainly achievable for libraries, frameworks, etc., it is a different beast for an application.

At the very least, and this is what our goal at work was before we started automating the release process, an automated release requires two manual approvals:

- To deploy to staging.

- To deploy to production.

So… Here’s how we release our services

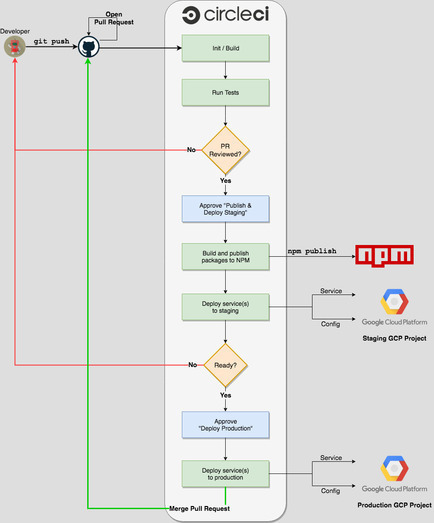

With the above in mind, the following diagram which I briefly mentioned in my first blog post of this series outlines our (mostly) automated release process:

As you can see, we use CircleCI. With CircleCI 2.0 and Workflows, the above translates to the following [.circleci/config.yml](https://circleci.com/docs/2.0/configuration-reference/) file:

version: 2

# Re-usable blocks to reduce boilerplate

# in job definitions.

references:

container_config: &container_config

docker:

- image: my-company/circleci:gcloud # We use a custom Alpine Linux base image with the bare minimum

working_directory: /tmp/workspace

restore_repo: &restore_repo

restore_cache:

keys:

- v1-repo-{{ .Branch }}-{{ .Revision }}

- v1-repo-{{ .Branch }}

- v1-repo

jobs:

build:

<<: *container_config

steps:

- *restore_repo

- checkout

- run: # Necessary to fetch / publish private NPM packages

name: Login to NPM

command: echo "//registry.npmjs.org/:_authToken=$NPM_TOKEN" > ./.npmrc

- run:

name: Install root dependencies

command: yarn

- run:

name: Bootstrap packages and services

command: yarn bootstrap # This runs `lerna bootstrap`

- run:

name: Build packages

command: yarn packages:build # This runs `lerna run build --scope '@my-company/*' --parallel`

- save_cache: # Now that everything is initialized and built, let's save it all to a cache

key: v1-repo-{{ .Branch }}-{{ .Revision }}

paths:

- .

test:

<<: *container_config

steps:

- *restore_repo

- run: # Here `--since remotes/origin/master` looks at the diff between `master` and the current PR branch. We only run tests for code we changed and its dependents.

name: Run tests

command: ./node_modules/.bin/lerna exec --since remotes/origin/master -- yarn test:ci # `test:ci` runs ESLint and Jest

publish_packages:

<<: *container_config

steps:

- *restore_repo

- checkout

- add-ssh-keys: # This is an SSH key with write permissions to our Github repo in order to `git push` changes.

fingerprints:

- "xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx"

- run:

name: Switch to the correct git branch

command: git checkout $CIRCLE_BRANCH

- run:

name: Configure git defaults

command: git config user.email "circleci-write-key@my-company.com" && git config user.name "CircleCI"

- run: # Temporary until we use Lerna's `--conventional-commits` flag (https://github.com/lerna/lerna#--conventional-commits)

name: Bump npm packages version (patch)

command: yarn packages:patch

- run: # Publishes each changed package to NPM, uses Lerna's `--parallel` flag to speed the process up

name: Publish packages (if applicable)

command: yarn packages:publish

- run:

name: Commit new versions to git

# This avoids the build from breaking if there are no changes to be committed.

# `git` exits with code 1 when there is nothing to commit.

command: git diff --quiet && git diff --staged --quiet || git commit -am '[skip ci] update package version(s)'

- run:

name: Push changes to Github

command: git push origin $CIRCLE_BRANCH

deploy_staging:

<<: *container_config

steps:

- *restore_repo

- checkout

- run:

# See https://circleci.com/docs/2.0/env-vars/#interpolating-environment-variables-to-set-other-environment-variables

name: Set job environment variables

command: |

echo 'export GOOGLE_AUTH=$GOOGLE_AUTH_STAGING' >> $BASH_ENV

echo 'export GOOGLE_PROJECT_ID=$GOOGLE_PROJECT_ID_STAGING' >> $BASH_ENV

- run:

# This is necessary because the `publish_packages` job may have pushed a commit with updated package.json files.

name: Pull the latest code.

command: git pull origin $CIRCLE_BRANCH

- run:

name: Copy .npmrc to the home directory

command: cp ./.npmrc ~/.npmrc

- run:

name: Authenticate gcloud CLI

command: |

source $BASH_ENV # 2017-12-21: That doesn't seem to happen automatically

echo "$GOOGLE_AUTH" > $HOME/gcp-key.json

gcloud auth activate-service-account --key-file $HOME/gcp-key.json

gcloud --quiet config set project $GOOGLE_PROJECT_ID

gcloud --quiet config set compute/zone us-west1-a

# Print for debugging

gcloud config list

# Note: The following `yarn deploy:*` scripts use `gcloud` to deploy services, configurations and the GAE dispatch file for URLs

- run:

name: Deploy services

command: |

source $BASH_ENV # 2017-12-21: That doesn't seem to happen automatically

yarn deploy:services

- run:

name: Deploy services config

command: |

source $BASH_ENV # 2017-12-21: That doesn't seem to happen automatically

yarn deploy:configs

- run:

name: Deploy the default service dispatch config

command: |

source $BASH_ENV # 2017-12-21: That doesn't seem to happen automatically

yarn deploy:dispatch

deploy_production:

<<: *container_config

steps:

- *restore_repo

- checkout

- run:

# See https://circleci.com/docs/2.0/env-vars/#interpolating-environment-variables-to-set-other-environment-variables

name: Set job environment variables

command: |

echo 'export GOOGLE_AUTH=$GOOGLE_AUTH_PRODUCTION' >> $BASH_ENV

echo 'export GOOGLE_PROJECT_ID=$GOOGLE_PROJECT_ID_PRODUCTION' >> $BASH_ENV

# Same as in `deploy_staging` above. Any better approach than copy / paste?

# PRs will be opened with package and/or service changes

# approval will be required to start npm versioning and publishing

# staging is deployed automatically FOR ONLY the current change for a given service

# NOTE: watch out for overlap when testing a single service and multiple PRs.

# Once services have been tested on staging approve deployment to production

workflows:

version: 2

build-test-and-deploy:

jobs:

- build

- test:

requires:

- build

- approve_packages:

type: approval

requires:

- test

- publish_packages:

filters:

branches:

ignore: master

requires:

- approve_packages

- deploy_staging:

filters:

branches:

ignore: master

requires:

- publish_packages

- approve_production:

type: approval

requires:

- deploy_staging

- deploy_production:

filters:

branches:

ignore: master

requires:

- approve_productionYou notice 7 configured workflow jobs, they correspond to the 7 rectangles in the diagram above.

The yarn deploy:* scripts we call during the deployment jobs are thin wrappers around the Google Cloud Platform gcloud CLI. The scripts run some validation and a bit of logic to deal with the staging vs production situation.

This is all pretty new for us. It works well, but we always look at ways to speed up the process or simplify it. One next major step is to integrate a way to automatically create CHANGELOG.md files for each package / service and let the system determine the appropriate semver version when publishing to NPM. Something like https://conventionalcommits.org/ looks interesting 🤔.

Conclusion

It’s been a great journey with ups and downs, but the end result is something that makes our day to day life simple.

Starting in 2018, each microservice will have owners, a team of at least two developers. Being a service owner follows the “You build it, you run it” principle. With the release process described in this blog post, each pull request gets deployed to production before it gets merged into master. The owners will be responsible not only for the development, but also for the service’s deployment, it’s monitoring and support.

Anyone at the company is free to open PRs in services they don’t own if there’s a bug. The service owners though will have the final word on approving PRs.

Let me know if you have questions, thoughts, suggestions etc about the above approach. I’d love to discuss and learn how others deploy to production.